Preserving Artwork:

How to Make Your Oil Paintings Last 100 Years or Longer

I preface the information below with the notion that if you follow common sense and are generally careful when handling, transporting, and displaying artwork, it should last indefinitely with minimal maintenance. The following bits of information are meant as guidelines and not as strict rules.

Artificial and Natural Light

For the maximum longevity of the color and flexibility of oil paintings the ideal lighting is a diffused natural or artificial light; the worst is intense, direct sunlight or ultraviolet light. Prolonged exposure (day in, day out, year after year) to direct sunlight or ultraviolet light will produce changes in the brilliance, hue, and balance of colors and will cause the paint to become brittle and crack or flake off. Even the most permanent colors eventually will be effected by this intense condition.

In general incandescent light is best. Fluorescent and halogen light are also good but produce slightly higher levels of ultraviolet light. LED lighting also seems promising, but testing is still being done to determine if there are any long-term issues. The higher the wattage, the farther away the light source should be so any adverse effects will be minimized. Keep lights of 100 watts or more at least 2 feet or further away, if possible.

When an oil painting is not exposed to light for a prolonged period (a couple of months or more in an unused, dark room or in closed storage), the linseed oil in the paints will naturally tend to darken or yellow slightly. This is a reversible condition. Just expose the painting to diffused natural light for a few days and it will regain its former coloration.

If your painting looks different in your living room than in the place you purchased it, this may be due to a number of factors. Variations in lighting type, intensity, and placement from that where you originally saw the artwork can create dramatic shifts in appearance. Incandescent light tends to be warm and yellow, fluorescents cool and blue, halogen a cross between the two, and natural light varies according to the time of day. A light that throws a very narrow beam or is very close to the work will create uneven light especially on larger paintings. Usually one or two spotlights about three or more feet away will create even lighting. The distance of the light from the work in conjunction with its wattage will effect how brilliant and saturated the colors appear. Also, the angle at which the light strikes the surface of the painting in conjunction with where the viewer stands can enhance or minimize the appearance of glare, color distortions, canvas texture, and brushstrokes.

The best way to find the correct lighting for your artwork is to stand where it will most likely be viewed and have a couple of people move lights around until the balance is perfect. You’ll only have to do it once.

Other factors to consider that effect the appearance of the painting are light brilliance, reflected light, and color of objects around the artwork. When you originally saw the work, did it hang on a dark blue or a cream colored wall? Was there a yellow rug reflecting bright sunlight or was there a dark wood floor reflecting almost no light?

Atmospheric Conditions

All parts of an oil painting expand and contract in reaction to atmospheric conditions. Since the paints, canvas, and frame expand and contract at different speeds and in unequal proportion, the painting is subject to stress. This stress can result in premature aging and damage to your artwork. The worst stress occurs during rapid changes in temperature and humidity. Gradual changes produce acceptable stress. The least stress occurs in a completely controlled environment (such as a museum) where the temperature is around 65 degrees and relative humidity is about 60 percent. Since most people do not have their paintings in a controlled environment, the best option is to observe some basic rules.

1) Avoid extremes of dryness, humidity, heat and cold such as directly under air conditioners, over radiators, heating vents, humidifier misters, and especially over working fireplaces. Also, avoid heavily used kitchens and unvented bathrooms. Warping of wood frames, cracking and flaking off of the oils, rotting of the canvas, and discoloration of the paints are the most likely effects of prolonged exposure to these conditions.

2) Avoid spaces (especially damp ones) that have little or no air flow. Air flow helps the artwork breath and prevents the buildup of moisture behind it which can eventually cause mold or mildew that invite discoloration, insects and rot.

3) Dust the work periodically (at least twice a year) using a soft feathered duster. If left undusted for years at a time the appearance of the artwork will be clouded and the dust can bond to the surface and require professional cleaning.

4) Cleaning of an oil painting should be handled by a professional. If your painting should be seriously soiled or tarnished with food, smoke, or other substances, do not attempt to clean it yourself. If small or minor cleanings are required, use ONLY lukewarm water and a cotton swab (lightly moistened) and GENTLY dab the paint surface. Avoid a dragging or pulling motion. Call the artist or a professional art cleaner/restorer if you are not sure how to handle a problem.

5) Linen canvas (as opposed to cotton canvas) can noticeably sag or loosen in the painting frame. This is a natural condition that occurs when relative humidity is high, most likely in summer months or in humid geographical locations. Often people will try to correct the condition by expanding the inner frame that the canvas is attached to by banging it out with a hammer or using an electric hairdryer to dry and tighten the canvas. DON’T, I repeat, DON’T try to correct this condition. It will naturally correct itself when the relative humidity goes down. Trying to correct it yourself will only produce a condition where, when the relative humidity goes back down, the canvas will tighten too much and the paint surface will crack and flake off. Also, NEVER moisten the rear of the canvas with a spray mister. Soaking the canvas will cause it to tighten like a drum and the paint surface will crack and flake off immediately.

6) Although not required, a coating of final varnish is highly recommended. It helps isolate the paint surface from an array of problems. These include dust, dirt, soot, carbon monoxide (which can cause certain colors to blacken), and ultraviolet light. Varnish can also give a more uniform appearance to the whole picture by evening out transitions from matte and glossy areas that occur in the painting process.

Varnishing should preferably be done by the artist or by a person trained to apply varnishes since it is very tricky to do correctly and disastrous if done incorrectly. In addition a painting must be completely dry before varnishing. Since oil paintings dry from the visible outer surface to the lower layers, a painting may appear dry to the touch when in actuality it may be far from completely dry. In fact, for thickly painted works it can take as long as two years to dry thoroughly. In general though, three months for thinly painted and six months for thickly painted works is a good rule. Note that any varnish will change the appearance of a work to some degree. It is best to see an example of a varnished and an unvarnished work before you commit your artwork to this treatment. Ideally seeing an example of a single work that is varnished on one half and unvarnished on the other will illustrate the effect of varnishing most clearly (*see additional notes at bottom).

Physical Damage

Physical damage (as opposed to chemical such as smoke or organic such as insects) is the most common form of damage to an oil painting. Because its front surface traditionally is not behind glass and its back surface is not against a mat board as would be the case with most drawings, the painting is very vulnerable, especially in transit or in hanging locations susceptible to moving objects such as people, pets, and wind. Scraping, dropping, puncturing, and tearing should be carefully guarded against. Also, never allow objects to press into or rest up against a painting’s surface (front or back). This commonly occurs when a painting is carelessly put in storage. Paint chipping and cracking are likely results as well as dent-like impressions that are almost always impossible to correct. Use extra caution when transporting a painting (attaching cardboard on both sides is acceptable, a custom-made transportation box is best) and chose a safe hanging location. Again, if your painting is damaged, consult the artist or a professional art restorer.

Organic Damage

Objects that produce organic damage are, for instance, mold, mildew, and insects. All three thrive in darkness AND moisture (darkness alone is generally not problematic). Insects can be present in any situation although the above one is most likely to attract them. The back of a painting, usually against a wall, is most susceptible since stagnant air and darkness collect there. It is best to follow the suggestions listed earlier under “Atmospheric Conditions”, Item #3 in order to minimize organic damage. It is also a good idea to check periodically behind a painting to see if there are signs of mold, rot, or insects. If there are, it might be a good idea to move the piece to a different location or air out the area behind and around the painting more frequently. If the problem looks serious, contact the artist or consult a professional restorer.

Notes on Varnish

According to Ralph Mayer’s “Artist’s Handbook” (see credits at end of this publication), a final varnish should meet the following requirements:

Protect the painting from atmospheric impurities,

Be elastic enough to withstand atmospheric changes,

Preserve the elasticity of the paint film beneath,

Remain transparent and colorless indefinitely,

Be reversible (i.e. easily removable),

Be non-blooming (i.e. prevent moisture build-up between the paint surface and the varnish

Be non-glossy.

According to Mark Gottsegen’s “Painter’s Handbook” (see credits at end of this publication), excellent synthetic varnishes are Liquitex’s Soluvar , Golden’s MS/UVLS (which inhibits ultraviolet light), Daniel Smith’s Picture Varnish (also with UV inhibitor), and Winsor Newton’s or Griffin’s picture varnish. These meet most of the requirements listed above.

General Notes

If you are interested in understanding more about the correct construction, preservation, care, and maintenance of any artwork, consult Jill Snyder’s and Joseph Montaque’s book, Caring for Your Art: A Guide for Artists, Collectors, Galleries and Art Institutions , which is very accessible to the lay person. If you are interested in a more technical book, Ralph Mayer’s Artist’s Handbook of Materials and Techniques is the definitive book on the subject. It has in-depth analysis of just about all art related subjects. Both these will probably be in your local library. If not, they are readily available for purchase at most art supply stores and online.

About this Information

Distribute freely – This information is distributed without charge and its redistribution is encouraged. The information is a combination of the artist’s personal experience and a loose interpretation of the following publications (unless quoted directly with an asterisk*).

Credits/References

(in order of influence on the artist)

Ralph Mayer – Artist’s Handbook of Materials and Techniques – 5th Edition – ©1991 Viking Press

Mark Gottsegen – The Painter’s Handbook – ©1993 Watson-Guptill Publications

Steven Saitzyk – Art Hardware – ©1987 Watson-Guptill Publications

Bernard Chaet – An Artist’s Notebook – ©1979 Holt, Rinehart, and Winston

Robert Massey – Formulas for Painters – ©1967 Watson-Guptill Publications

Ian Hebblewhite – Northern Light Handbook of Artist’s Materials – ©1986 Quarto Publishing

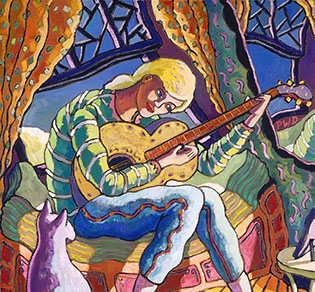

Composer 1 - Peter Diianni 1997

Davis & Einstein - Peter Diianni 1999

Drumming - Peter Diianni 1998

Sarah's Song- Peter Diianni 1998

Blue Jazz - Peter Diianni 1995

Isabel - Peter Diianni 1999

Queen of Clubs- Peter Diianni 2000

Saxman - Peter Diianni 1999

Solo Trumpet - Peter Diianni 1999